Why I Left the Right: How Studying Religion Made Me a Liberal

It was January 20, 2001, and I was at George W. Bush’s inaugural ball. I had spent months campaigning for him, and it had not been easy. After the Florida electoral debacle complete with “hanging chads,” Katherine Harris (and her fifteen minutes of shame), and ultimately the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore decision, I was finally enjoying the fruits of my labor as I celebrated the new president that I worked to get elected.

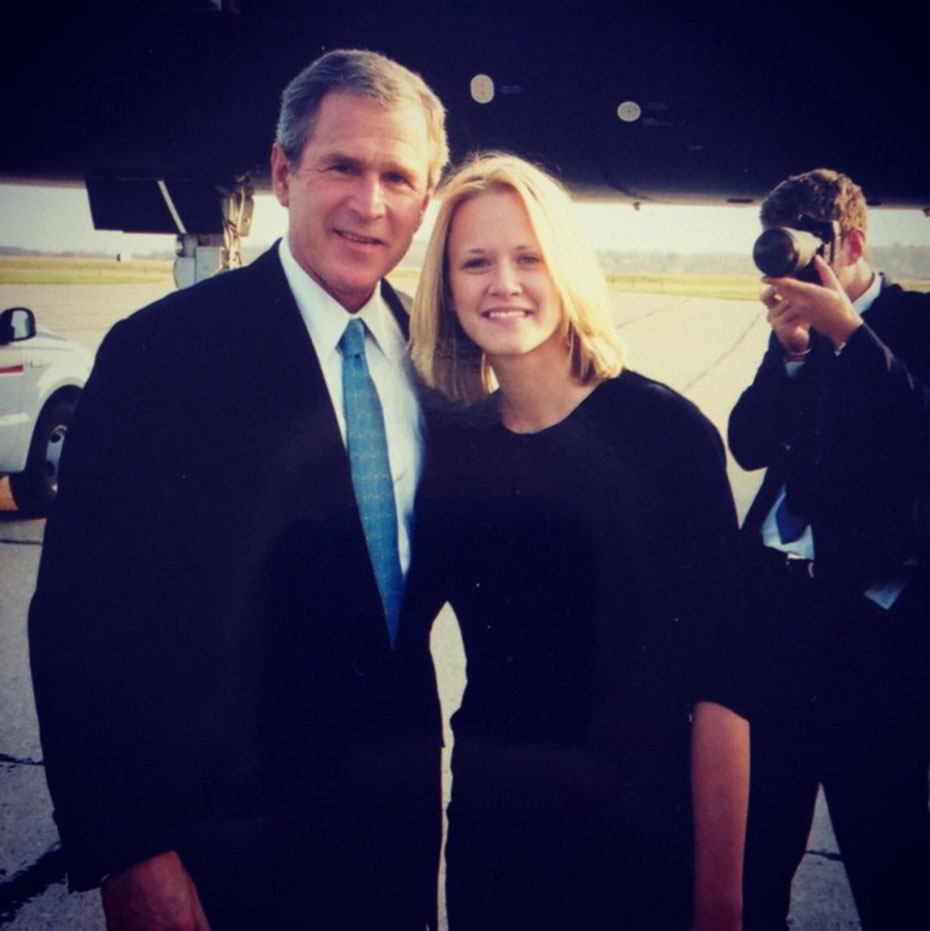

My role in the campaign wasn’t glamorous, but I was a twenty-year-old political science, religious studies double major who saw this election as the beginning of my work for the Right. I had recently appeared on MTV’s reality show, Road Rules, where I represented the worldview of conservative evangelicals in all its virginal, Christian glory in a very public way (complete with an episode detailing my “downward spiral” that amounted to me swearing once and stealing a pair of bowling shoes). Now I wanted to turn my moment in the spotlight into something meaningful.

During the campaign, I attended Young Republican meetings, drove Bush’s trusted advisors, Andrew Card and Karen Hughes, in the motorcade when they came to town, and now I was working the inaugural ball as the celebrity handler for special guest, Drew Carey. During the evening, he admitted that he wasn’t actually a Republican, but a libertarian. “Good enough,” I thought to myself, “As long as he isn’t one of ‘those liberals.’” I believed my involvement in the campaign was just the beginning of my efforts to promote the conservative movement and perhaps my own career as well.

Growing up immersed in the evangelical community, I was so familiar with the Christian rhetoric and worldview that it never occurred to me that they might be getting it all wrong. During the late eighties and throughout the nineties, evangelicalism hit its stride communicating and promoting a very specific message that amounted to a chorus of sound bites about “family values,” militarism, and the pro-life movement. The group’s unified theological positioning inspired the mobilization of American evangelical voters, and influenced countless election results.

As I stood there in my purple satin, floor-length gown and then-in-style white eye shadow watching the new President dance with his First Lady, I was inspired by what I thought was a going to be a move toward increased personal responsibility, a shift from the distracting Clinton/Lewinsky circus, and a return to the philosophy of the patron saint of right-wing politics, Ronald Reagan. What I didn’t realize was that I soon would become one of “those liberals,” and that the very thing that inspired my conservatism, would now be the thing that caused it to topple: my faith.

I was more than just your garden variety Christian; I attended church several times a week, sought guidance from my pastor in private meetings, and after my reality TV stardom, spoke to church youth groups about how to stay “pure” in this “sinful” world. As I began studying religion at the University of Pittsburgh, people in the church warned me about what could happen under the influence of the liberal intelligentsia. The bias of “godless liberals” teaching at universities was reason enough to avoid traditional education. I believed them when they said academia skewed to the left, but surely a faith as strong as mine could stand up to academic scrutiny.

What happened, however, wasn’t an abandonment of my faith, but a shift in my understanding of Scripture. While I had always read the Bible and knew large portions of it by memory, I had relied on the expertise of my religious mentors (some of whom were simply laypeople teaching Sunday School or Christian education classes) to help guide me through its interpretation. The more I read the text through unfiltered eyes and the more I learned about scholarly investigation, the less sense their point of view made. Their old Jesus looked nothing like my new Jesus.

I could no longer reconcile Jesus’s calls for non-judgment, loving your enemies, and taking up your cross with many of the Religious Right’s positions on social services, women’s rights, and the LGBT community. Even though I felt alone in my theological shift, I was not. A recent Pew Research Center poll puts the evangelical retention rate at 65%, and while we don’t know to what extent education plays in the decision of a believer to leave a tradition, I suspect the fears of many of my religious peers regarding secular education were not unfounded. It isn’t just general education that can shift beliefs; indeed a recent study by Baylor University researcher Aaron Franzen found that increased reading of the Bible correlated with greater passion for social justice — a trait typically associated with liberalism.

Having my worldview fall apart like a house of cards was unnerving, but it only increased my desire for knowledge about the theology of my youth. I continued to study religion, and I received my PhD in Religious Studies two years ago. Now I no longer identify as an evangelical, but I study them for a living.

Only after my doctrinal evolution did I realize I no longer aligned with the political conservatism for which I once literally campaigned. Jesus was a champion of the poor, the weak, the meek, and downtrodden. He encouraged his followers to “sell their possessions” and give them to the poor. He hung out with hookers and crooks. The lifestyle of Jesus didn’t look anything like the politics of the Right.

My transition to the left didn’t happen overnight, and sometimes I felt like a deserter. The man whom I worked to get elected no longer represented my politics or my piety. As I continue to observe the curious twists and turns of evangelicals, particularly during this election year, I remain fascinated by the ways they reconcile their theology with their policy. Evangelicals do not represent a monolith, but they traditionally align with conservative politics. Much has been made of Donald Trump’s evangelical supporters due to his personal life reflecting anything but the “family values” they espouse, but Christians often choose the policy over the person. From Ronald Reagan’s divorce to Mitt Romney’s Mormonism, evangelical Christians give passes to those whose rhetoric is most in line with their philosophy and who they believe can win the election, even if that person’s biography isn’t in line with their religious doctrine.

My journey from Young Republican to less young Democrat did not come from a crisis of faith, it came from finding inspiration in the life of Jesus. Once I removed the dogmatic lens that had informed my biblical interpretations I found a figure that defended a prostitute and ate with the poor. The life of Jesus simply didn’t reflect the agenda of the political right, so now neither could I.

Susie Meister is a PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Pittsburgh. Her research focuses on media and religion in America. She is a cast member on MTV's The Challenge and co-host of The Brain Candy Podcast. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband, Adam, and their son Lincoln